country introduction

What distinguishes the country?

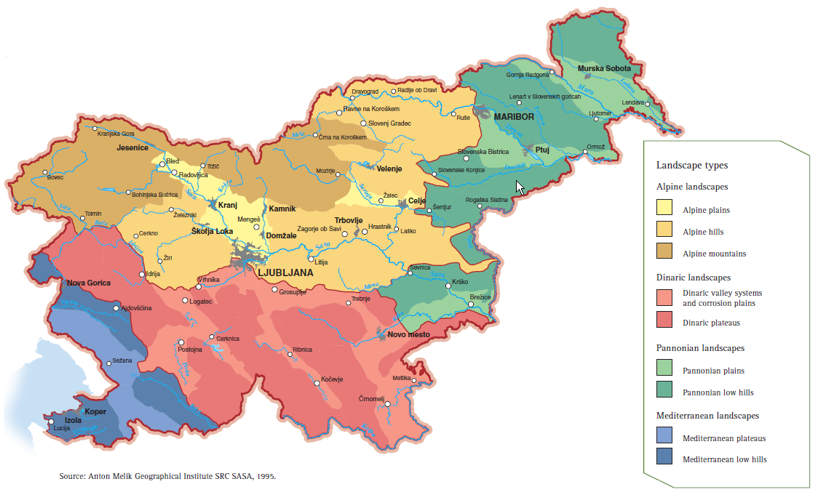

Slovenia is exceptional for its diversity of terrain, with four major natural units merging in this small part of Central Europe: the Alps, Dinaric Alps, Pannonian Basin and the Mediterranean.

Interweaving of ecoregions

Slovenia is exceptional for its diversity of terrain, with four major natural units merging in this small part of Central Europe: the Alps, Dinaric Alps, Pannonian Basin and the Mediterranean. The variety of rock strata, topography and climate, plus their mutual influences, give rise to exceptional diversity of soil and biology.

Slovenia ranks among the better-watered and largely spring-fed countries, with a dense river network, a rich aquifer system, and significant karstic underground watercourses. At the same time, four linguistic and cultural regions meet in this territory: Slavic, Germanic, Romance and Finno-Ugric (Hungarian).

Figure 1: General map of Slovenia

Source: Surveying and Mapping Authority of the Republic of Slovenia, 2002

Figure 2: Natural regions in Slovenia

Source: Environment in the palm of your hand: Slovenia, 2008

Slovenia has a moderately warm and divers climate.

Contact point of Mediterranean and continental climates

Slovenia has a moderately warm climate. However, in line with its geographical diversity, it is very diverse. Meeting above Slovenian territory are the influences of the Mediterranean climate, which is characteristic of the coastal part of Slovenia; the continental climate typical of the central part of Slovenia and the Pannonian region to the east; and the Alpine climate in the northwest of the country. The level of precipitation is sufficient across most of Slovenia, and does not vary seasonally. It is highest in the Alpine area to the west, with more than 3 000 mm/year, and this declines to the east, where it is lowest, amounting to around 800 mm/year, while, overall, the average is between 1 400 and 1 500 mm/year. Along the Adriatic coast the precipitation level is lower than the average, and lower in summer than in winter. In winter it is normal for snow to cover all the continental regions, and in the Alps, given the high amounts of precipitation, the snow cover can reached 9 m at the Kanin ski resort in 2009 - by the sea any snow cover is exceptional. In the summer, especially in June, July and August, the greater part of Slovenia typically experiences a large number of storms - around 50 each year, the highest amount in Europe.

Figure 3: Mean annual precipitation, 1971-2000

Source: Environment in the palm of your hand: Slovenia, 2008

Basic facts

Independence and the EU

The Republic of Slovenia is a parliamentary democratic republic that became an independent state after the disintegration of Yugoslavia in 1991, and joined the European Union in May 2004.

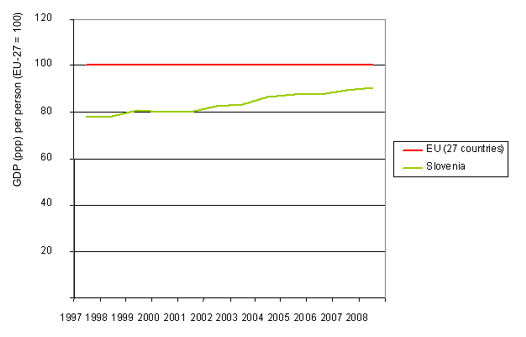

Since independence in 1991, Slovenia's economic development has been successful, making it one of the most thriving countries in transition. On 1 January 2007, Slovenia became the first new EU member to adopt the Euro, and in the first half of 2008 successfully held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union.

Polycentric approach

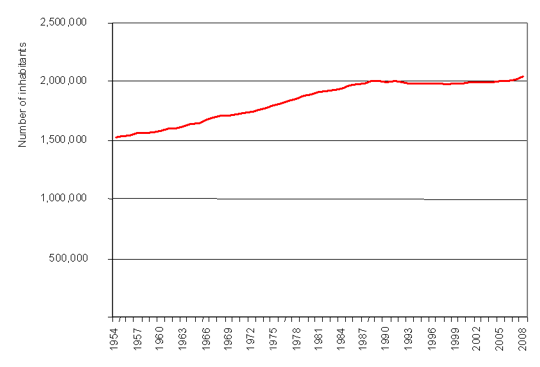

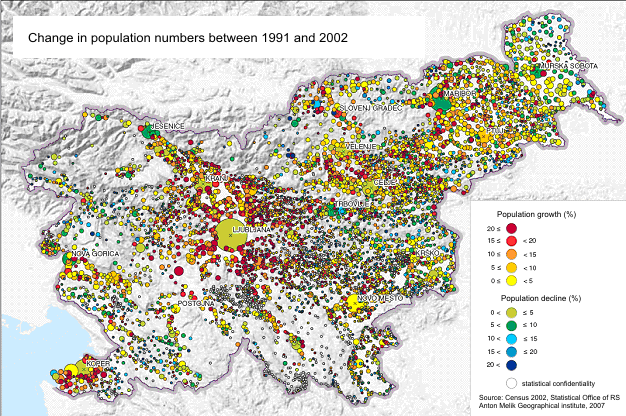

Slovenia's surface area measures 20,273 km2 and covers part of the sea in addition to its land territory. It is home to just over 2 million people in a little under 6 000 settlements. Half live in small settlements with fewer than 2 000 residents, and only Ljubljana, with 276 000, and Maribor, with 113,000, are the only cities with more than 100 000 inhabitants. Average population density is 99 people per km2, but the great topographical variation means there is uneven settlement, with the concentrations in the lowland areas of Alpine valleys, the Pannonian Plain and the coastal area, and this is increasing.

Environmental management

The drafting of strategic documents and legislation to ensure a healthy living environment and sustainable development is a task assigned to the Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning, and their implementation, including the issuing of permits and monitoring of the state of the environment, is the task of the Environmental Agency of the Republic of Slovenia (ARSO). A supervisory role is also played by another body attached to the ministry, the national Inspectorate of the Republic of Slovenia for the Environment and Spatial Planning.

Ensuring the drinking water supply, treatment of municipal wastewater and the managing of municipal waste and some natural resources of local importance, including spatial planning, fall within the jurisdiction of local communities - the 210 municipalities.

Figure 4: Number of inhabitants of Slovenia 1954–2008

Source: Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia

Figure 5: Change in population numbers between 1991 and 2002

Source: Census Atlas of Slovenia 2002, Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2007 (in Slovene language only)

Figure 6: Population density

Source: Environment in the palm of your hand: Slovenia, 2008

What are the major societal trends?

Slovenia a successful new EU member state

Historical background

Central planning and self-management socialism

From the end of World War II until independence in 1991, Slovenia was the most developed of the six republics of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

Aspirations for more balanced development of economic sectors and thereby smoother involvement in international trade, better provision for the population and greater prosperity appeared as early as the 1950s. Development was geared towards manufacturing and high-technology industry, such as chemicals. Regional spatial planning was implemented as part of social planning, with towns expanding primarily around industrial centres, and in the 1960s the main trends of settlement followed this path. In the 1970s, however, people started moving back to rural areas close to the towns. The prospects of employment in industry also changed the proportion of the farming population, which fell from 49 % in 1948 to 12.5 % in 1981. Owing to the major energy potential of rivers, even in the 1950s the management of water by river basins was in place. The entire post-war period in Slovenia has been marked by polycentric development and large-scale daily commuting to work.

Transition and restructuring

Following independence in 1991, Slovenia lost a large part of the Yugoslav market, which caused the collapse primarily of heavy industry and the previously low unemployment rose significantly.

Restructuring of the economic and social system enabled higher economic development after 1995, with investment in the road transport infrastructure, commercial and residential buildings, while privatisation also caused greater social stratification. The restructuring of Slovenia's economy was marked by its slow pace and by the fact that to a large extent it was based on emission-intensive industry (OMAD, 2009). Particularly after Slovenia joined the EU, the newly built motorways significantly increased transit goods traffic, on the border with Hungary by as much as 112 % in the period 2004-2007. Today around 8 % of the population are occupied exclusively with agriculture (SORS, 2009), and additionally a large proportion of farmland is cultivated by people with a second source of income. It is significant that in the majority of agricultural areas extensive forms of agriculture have been maintained, preserving a high level of biodiversity and the landscape with its rich cultural and natural heritage. Owing to the wealth of natural features, history and cultural attractions, tourism is also growing.

In the period since 1995, the economy has grown by an average of 4 % a year, closing Slovenia's development gap with the EU average. In 2008, gross domestic product (GDP) per person in terms of purchasing power parity (ppp) reached 92 % of the EU average. While the economy grew, unemployment fell - in 2008 registered unemployment stood at 6.7 %. The Slovenian economy has a high industrial component in total generated value added, and within this there is a high proportion of energy-intensive activities and a low proportion of high-tech ones. Strengthening those activities with higher value added per unit of production is progressing slowly (OMAD, 2009).

Figure 7: Development of goods transport (road traffic – tkm of Slovenian transporters at home and abroad; rail transport – net tkm on the Slovenian network; maritime transport – t of goods transferred at the Port of Koper; air cargo – t of goods transferred at airports)

Source: Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Slovenia, Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2009

Figure 8: Comparison of GDP (ppp) per person between Slovenia and EU average

Source: Development Report 2009, Institute of Macroeconomic Analysis and Development of the Republic of Slovenia, 2009

What are the main drivers?

The natural regions into which Slovenia is divided differ in their level of vulnerability to environmental threats, and also in the type of environmental pressures they face.

The natural regions into which Slovenia is divided differ in their level of vulnerability to environmental threats, and also in the type of environmental pressures they face.

Slightly poorer quality air in Alpine basins and valleys

To the north of Slovenia lie the Alps. The mighty limestone and Dolomite Mountains of the high Alps are separated by deep, glacially-formed valleys, and are largely uninhabited. To the south and east they continue into somewhat lower, but similarly separated Alpine foothills, overgrown with forest and scattered with isolated farms and villages. The gravelly bottoms of the Alpine valleys are extremely abundant, yet, owing to dense settlement, intensive farming, large-scale transport and numerous other factors, have very vulnerable watercourses - the Alpine rivers, chiefly the Drava, Sava and Soča, are an important source of hydroenergy. Winter temperature inversions, which are typical of Alpine basins and valleys and obstruct the mixing and movement of air, exacerbate the problem of ensuring high-quality air. Pollution with PM10 particles is particularly problematic, to a large extent the consequence of industrial pollution, and, in larger urban centres, of traffic.

The ecologically sensitive Adriatic Sea

In the far west, the Alpine area touches the Mediterranean near the Gulf of Trieste. The shallow Slovenian sea is ecologically very sensitive and reacts quickly to pollution, for instance from excessive outflows of nutrients from rivers, untreated municipal wastewater and the negative impacts of intensive maritime transport, which are a consequence of the increasing density of the population, transport, industry and tourism in the narrow coastal belt. The scant rainfall in the summer months, which is also the main tourist season, dictates the most frugal use of drinking water and concern for the adequate quality of bathing water. The coastal Primorska region also ranks among the most ozone-polluted areas of Slovenia, particularly in the hot summer months. This is mainly a consequence of the transfer of pollutants from the nearby Po Valley in Italy.

High-quality but vulnerable karstic underground watercourses

Towards the east the Mediterranean region merges into the Dinaric Alps with their high plateaus, Dinaric valley systems and tablelands. This region, especially the extensive Dinaric plateaus, has few surface watercourses owing to its karstification, but has an evolved underground system of karstic caves with extraordinary biodiversity and stocks of water, and is covered in extensive forests. Owing to the sparse population in karstic areas, the underground water is mainly clean and is an increasingly important source of drinking water. However, cases of long-term contamination of karstic springs, which resulted from ill-considered dumping of hazardous substances in the hinterland, is a reminder of their extreme vulnerability. Challenges for maintaining extensive protected areas included in Natura 2000 are posed by the need to develop peaceful cohabitation of people and large predators - bear, lynx and wolf - and by the development of important transport and commercial infrastructure.

Intensive farming on the Pannonian Plain

In the east of Slovenia is the Pannonian region, a densely inhabited and intensively cultivated area. Meandering slowly through the Pannonian Plain are some major rivers, which represent an important source of hydroenergy. Agriculture is an important social component of this region, and is highly dependent on natural factors, so there is a need to adapt to climate change, which is evidenced by droughts and extreme weather phenomena.

Greater consumer impact on the environment

The modern way of life and the impact of the consumer society have brought the whole of Slovenia face-to-face with increased quantities of waste. Greater efforts will be needed to deal with it - especially in municipal waste management. Diffuse settlement, daily commutes to work, the construction of shopping centres on the outskirts of settlements, increased transit traffic through Slovenia, intensive construction of the road transport infrastructure and neglecting other forms of transport translate into a large number of problems. Additionally, as a result of inadequate restructuring of the manufacturing sector following the introduction of a free-market economy, Slovenian industry is still showing low energy and environmental efficiency, and there are also problems in implementing IPPC directive.

Figure 9: Land cover in Slovenia

Source: Environment in the palm of your hand: Slovenia, 2008

Figure 10: Quantities of recovered and removed waste by method of handling

Source: Waste Management Database, Environmental Agency of the Republic of Slovenia, 2009 (Ref: Environmental Indicators in Slovenia, OD07)

What are the foreseen developments?

Slovenia achieved good economic and social development, but did not sufficiently exploit these good times to implement the structural changes necessary for achieving the strategic development goals, including those for the environment.

The Slovenian Development Strategy

The Slovenian Development Strategy for 2006-2013 defines four basic development goals:

- economic development - in ten years to exceed the average level of economic development in the EU;

- social development - to improve quality of life and prosperity;

- intergenerational and co-natural development - to implement the principle of sustainability in all areas of development, including sustainable population renewal;

- Slovenia's development goal for the international environment - to become a recognisable and respected country in the world.

The latest report on implementation of the strategy states that in the period of booming markets, Slovenia achieved good economic and social development, but did not sufficiently exploit these good times to implement the structural changes necessary for achieving the strategic development goals, including those for the environment. The challenges remain: reducing greenhouse gas emissions, increasing the use of renewable energy sources, recovery of waste, appropriate management of municipal waste, etc.

Future development, especially in the light of climate change, has been presented as being slightly slower and different in the three scenarios drawn up by The Government Office fpr the Development.The development scenarios up to 2035 formulated were:

No ideas - this scenario presents a predominant lack of any appropriate action by governments and their denial of any kind of environmental impact. Increasing extreme weather phenomena and negative impacts will ultimately lead to the adoption of harsh and stringent measures. There is no technological development, so Slovenia becomes a place to which dirty technology moves from, for instance, Asian countries. The EU is in a similar situation. In this scenario the decision-makers do not understand the impacts of climate change, so tangible steps are taken only when they may be too late.

Green oasis - the best result can be achieved through early measures driven by technological change and changes in values. The population accepts all the plans and recommendations, policies and regulations are implemented to the greatest possible extent and thus the consequent benefit is maximised. The economic system changes and becomes less carbon-intensive. This scenario is the one in which the world is ahead of the impact curve, whereby to the greatest possible extent the effects of climate change are reduced and prevented. The fulfilment of this scenario requires global cooperation, consensus and harmonised policies for a long period of time.

Chameleon - this is the story of evolution: small, individual adjustments and responses are made to deal with the impacts and consequences of climate change without few attempts to prevent negative impacts in the long term. Measures are adopted, but without coordination. The world heads in the right direction, because people feel that a strong response to climate change is needed, but it is still insufficient and too late to avoid exposure to forces that are the consequence of climate change.